Experiments have the power to make a huge difference in how you run a subscription business. With that power comes the flip side: the potential to damage your brand, compel you to try unethical things, and maybe even lose you a lot of money.

This article explains experimentation and shares the key experiments I’ve run over the last 10 years leading Paid Memberships Pro. My goal is to help you identify one experiment to run in the next 30 days for your subscription website.

This article is a companion to my presentation for the 2021 WPMRR Virtual Summit on Wednesday, September 22. Download the presentation »

I’ve been running experiments for a long time.

For context, I do personally run a recurring subscription business. And my product is a platform for WordPress that helps people start recurring subscription businesses. So my knowledge is informed through personal experiences as well as things I’ve observed through my customers.

But first, know that this is not a guide on the tools that help you run business experiments.

Experimentation doesn’t have to be a formal process. So don’t focus on running a perfect experiment.

Each experiment needs different reporting and analysis: some are more robust, while others can be “quick and dirty”.

If you’re just getting started, don’t overwhelm yourself and try to control everything. Yes, make sure you aren’t pulling too many levers and tweaking too many things—some factors must be in the “control group” if you want to get all scientific.

Just focus on running a somewhat controlled experiment.

So, what is an experiment?

100% of decisions are made without 100% perfect information. So when you think: “What is an experiment?”, think “an experiment is anything that tests a hypothesis and gives me data to help make decisions”.

Put differently, experiments test your assumptions to help you make better decisions.

As business owners, we are navigating the world of information overload, with ideas streaming in from a bunch of places.

- user, customer, and team feedback

- advice from other business leaders

- something you heard on a podcast once

- stuff you observe about your competitors

- your personal ethics, knowledge, experiences, and, a highly underrated aspect, gut instinct

- …plus some deep hopefulness and finger crossing (or holding thumbs if you live in South Africa)

Here’s an example of how you might be making decisions.

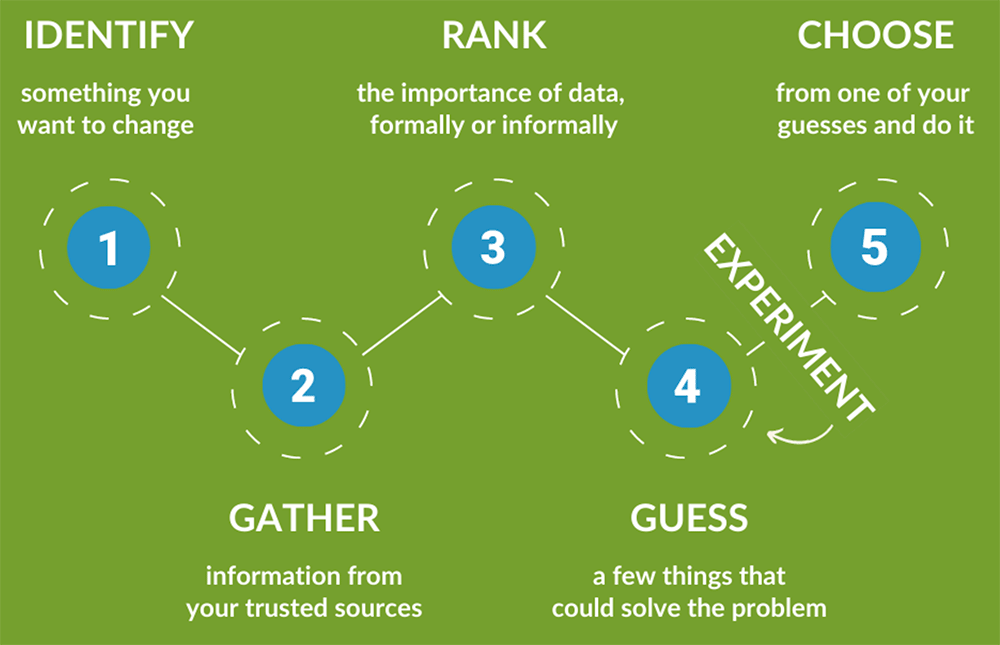

- Identify something you want to change

- Gather information from all of these inputs

- Informally or formally rank their importance

- Make a few educated guesses on what to do

- Choose one and decide do it

In each step of that process you could probably identify over 100 things that you’ve assumed. And you know what people say about assumptions 👀

When you add experiments to your business, you insert an activity between steps 4 and 5. Before you reach a final decision, you test the choice. If the experiment gives you the right confirmation you need to make a change with confidence, you can make the change and move on. Or, you run another experiment.

Experiment: Simplifying Prices

Here’s a personal story, one of many I’m going to share. It focused on pricing and the renewal rate for our most popular membership level, Plus.

We’ve been changing our prices every few years since we started Paid Memberships Pro in 2011. Since then, we always front-loaded the initial year of membership, and lowered renewal rates for years 2, 3, 4 and so on. As the pricing settled into something that felt right, we offered our most popular membership level at $297 for the first year and $197 for every year following. And we operated that way for a couple years.

The problem was: people were confused. The levels page, the checkout page, their membership account page all said $197 per year. We tried to “get smart” and never show a logged in user the “first year” price, and instead updated it everywhere to just show what their next renewal price would be.

This meant that people would buy Plus, somehow end up back on the pricing page and see the price $197. Then they would email me and say “Hey, you, I paid $297 but now it says $197. I want my $100 back!”

By front-loading our pricing, we had made it unclear what the user would be charged, when.

And what’s worse is that we were possibly leaving money on the table.

In May 2019, we ran a month-long experiment where we just changed the pricing to be $297 per year, every year, no discount on renewal. I literally edited the membership level, changed the annual recurring rate to $297, and hit save.

Guess what happened? There was no impact on conversions. So the “experiment” became the new price.

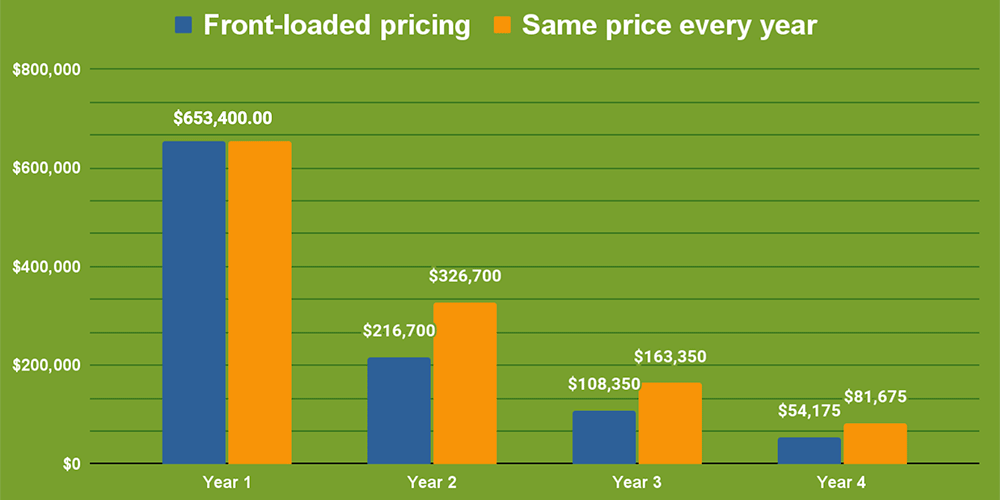

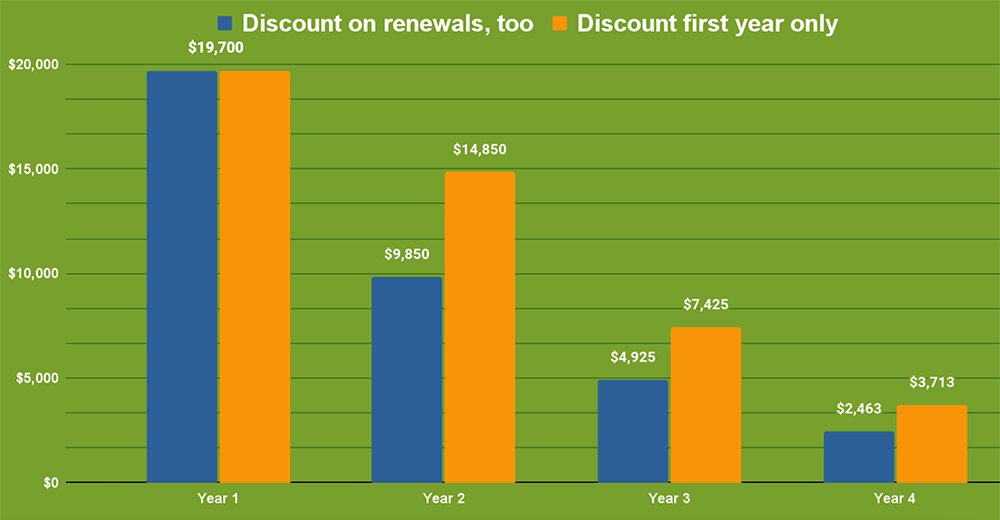

The chart here shows an example of 4 years of revenue for the old and new pricing model. This assumes 2,200 new members per year (we get more signups, now, but that was closer to our 2019 number) and a 50% retention rate (ours is a little better).

And then we waited, again. We waited until May 2020 to see how this higher price would affect retention rates.

They stayed the same.

We are now getting more value from our users—making 33% more revenue for every renewal payment.

The data from this experiment and how we changed pricing adds an additional $192,500 in revenue for the three years following the change.

PLUS the change reduced confusion for our customers and reduced admin overhead. No more “what the heck?” emails.

Front-loading is a valid pricing strategy, and if we’re honest, our product really does deliver more value in the first few months.

If you’re thinking about adjusting pricing, you can also consider testing the opposite. Say you’re charging $50 per month for your membership, but you find customers canceling after two to three months. Consider instead charging $150 upfront and $20 per month after that. The $150 will match the lifetime value you were getting before. And while raising prices means fewer sales, you’ll often make more money overall. Experiment to find the specific numbers that work for you.

So what kinds of things can you experiment on in a subscription business?

The most obvious place people look to experiment is price. Price experiments give you endless opportunities to test assumptions and tweak your model. And, most importantly, help you grow revenue.

I just shared the experiment on renewal pricing. We’ve done a few other price experiments over the years including faking a price increase.

In August 2017 we decided it was time to raise prices. Over time our product was getting a lot better. We had more premium Add Ons. Our support was faster and more technical. We were trying to grow our team and hire more dedicated developers and pre-sales team members. Not to mention that we were the least expensive (ahem, and best) option among our competitors in the WordPress space.

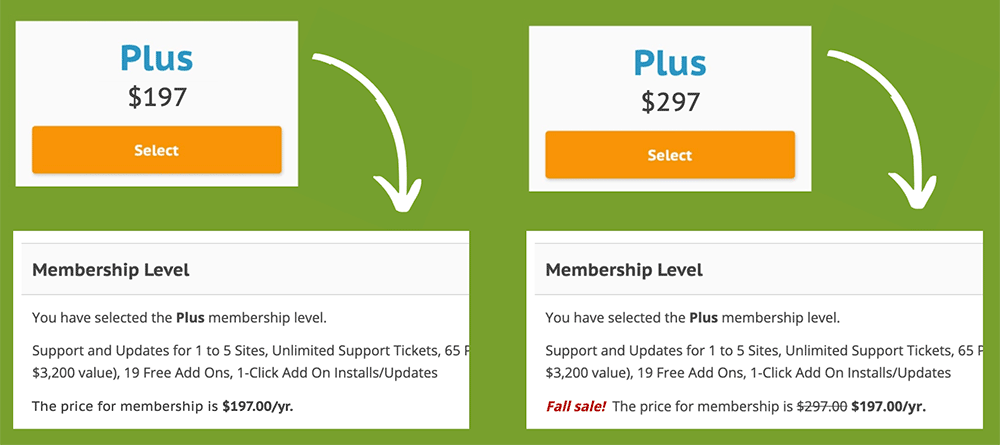

So before we increased the price of our Plus level from $197 to $297, we tested the price increase. We ran an A/B test. Half of our visitors saw the $297 price everywhere on the website except the checkout page. At checkout, we truly charged this half of users $197 and displayed a message about a secret “Fall sale”.

We weren’t testing how many people would complete checkout at the higher price. We were experimenting on how a higher price changed the number of people clicking through to our checkout page from the pricing page.

This isn’t a perfect test. But for an imperfect test it gave us a tiny bit of validation that changing prices wouldn’t drastically reduce the number of people hitting the checkout page. So we confidently raised prices, still always honoring historic lower prices to old members and anyone that came and asked.

There is so much you can experiment on with pricing.

But don’t stop here! There are so many other areas you can experiment with. Things like

- Sales, discounts, and promotions

- Your sales funnel, marketing strategies, and site layout

- Testing Products or Services

- How you offer support, and even

- How you operate and grow your Team

Experiment: Homepage CTA—where to?

Here’s a marketing experiment we ran in 2016 for our homepage “call to action” (CTA).

We have this firm belief that a homepage should do one thing. Especially in a membership type product where the goal is sign ups.

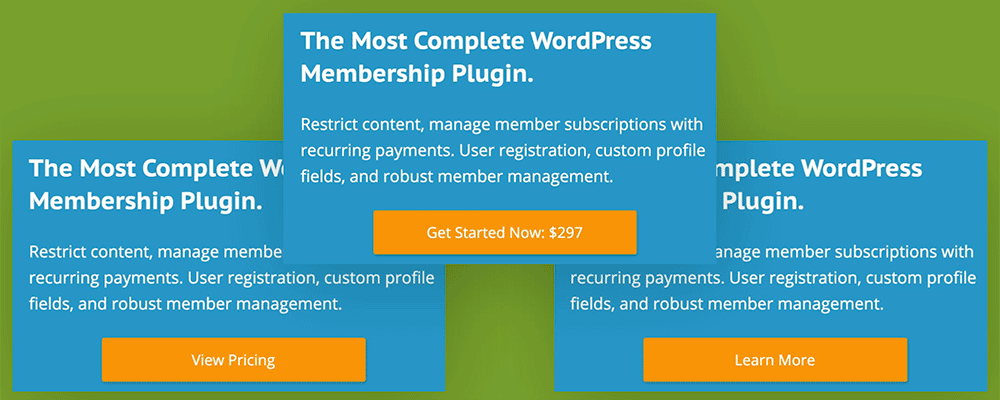

Like most homepages, our main banner shows a video, short blurb, and button. In 2016, we experimented with where our CTA button linked to.

We tried three options:

- a “learn more” button where users were taken to a features page,

- a “view pricing” button where users were taken to our levels comparison page, and finally

- a “get started now” button that included the price of membership and linked directly to checkout for our most popular membership level

We ran this experiment with some custom A/B testing code. We also added a few Goals to our Google Analytics account so that we could visualize the funnel of users that completed checkout, what pages they visited prior, and where they disappeared.

Through that experiment, we learned that the more users we push to our Plus membership checkout page, the more users we can convert. After that experiment, we left “Get Started Now” as the only homepage CTA button.

Then just a few days before I was preparing this content, Jason gathered new data about our goal. We realized it’s time to run a new experiment on that homepage CTA. Which leads me right into the next thing I want to say about business experiments…

Test what is working, too.

Don’t just test what you are struggling with. You also have to test what you believe is working. Even the things that are working really, really well.

If you haven’t seen it, this concept is kind of like the Continuous Improvement Process.

To oversimplify, continuous improvement in business is a mindset that everything can and should be improved upon. You and your team readily embrace new ideas, hypothesize, run tests, reflect, and make meaningful changes.

Always be testing. Be on the lookout for opportunities to run tests when you’re making changes to your website or product, or anything else. If you are making changes, think “is this decision based entirely on my assumptions?” And if the answer is “yes”, you can either trust your instinct or go get some information out of a new experiment.

I want to share another experiment—this one is an active experiment so come find me in August 2022 if you want to see how it went. This is an experiment around sales, discounts, and promotions.

Experiment: Sales—Discount First Year Only

We run a few sales every year, primarily timed to boost revenue in slower months.

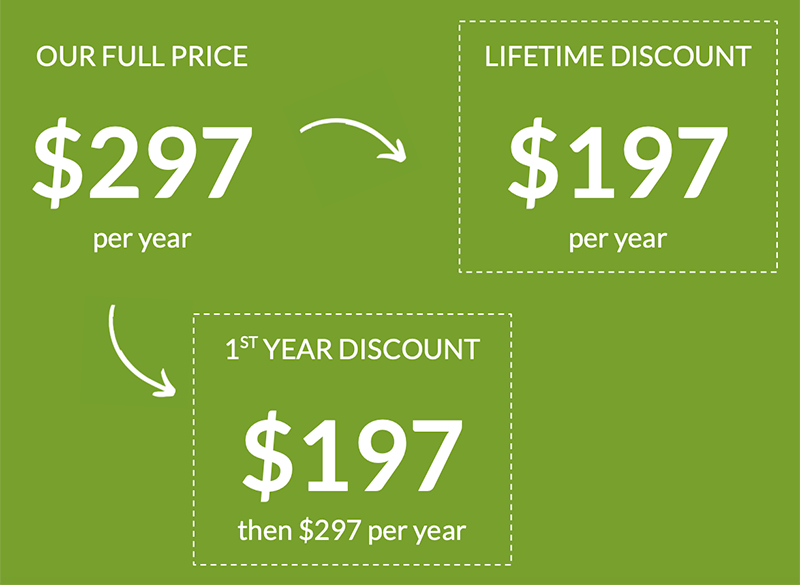

I talked earlier about how we ran an experiment and decided to simplify pricing. Everyone pays the same price every year, no front-loading and no renewal discounts. In this experiment, we decided to “back-load” our price. Let me explain.

Every sale we have ever run was the same: your discount is locked in for the life of your membership. We would offer a $100 discount on the first year, and every year following.

$197 per year if you bought during the sale.

Then we hired Patrick and his jaw quite literally dropped. I’m serious. He couldn’t believe we were offering lifetime discounts with every sale. It was unheard of in his business experience and he strongly felt that we were leaving money on the table. Lots of money.

In an average week long sale, we have around 100 new member signups. Discounting renewals was leaving almost $10,000 on the table over the next few years, assuming a 50% retention rate. Multiply this by 4 sales per year and that pile of money of the table grows pretty fast.

So we had a sale at the end of July and changed that policy. We let our team challenge our assumptions.

- I assumed people would get angry that the discount wasn’t recurring. It was the wrong assumption. No one emailed us after their purchase and asked why the price is $100 more next year.

- I assumed it would be hard to write the sales copy that made it clear what people were paying, when, and for how much. Wrong again. We had the discounted price on display, the line below it said “then, $297/yr.” and we even put an additional sentence about the discount on first year only at the end of the form. Their confirmation emails clearly show that the recurring membership is the full price. I wasn’t trying to be sneaky, so it was easy to make this information all clear

- This sale performed better than most seasonal sales we’ve run in the past. I think it’s safe to assume that removing a recurring discount didn’t noticeably impact conversions.

- I still have a small assumption that people will reach out next year when they renew and ask to pay less. While I won’t know whether my assumption is correct for many months, I do know that if they ask, I’ll give them a discount. At a $197 renewal, we are still profitable.

Are business experiments safe?

Ok, I recognize that this is a vague question. The answer is, of course, some are and some are not.

I want to talk about “experimenting safely” because if you screw this up you can do some permanent damage to your brand. You can damage personal and business relationships within your team, with your customers, and with your peers.

You could also lose money. So you have to think of a business experiment as an investment.

I’m going to asterisk and footnote this whole section, though, for the very early days of your subscription product. While you should never do anything outright illegal, in the launch phase, it is ok to experiment and possibly upset the small number of early buyers.

We had to pivot our pricing in the first year. I think our first pricing for Paid Memberships Pro was $10/month. That was the absolutely wrong price. People were getting loads of help then cancelling in month 3. We had to move these people into annual plans and remove that payment option.

So with safety in mind, remember that a healthy experiment:

- Has a start and end. Experiments should not run forever, so when you set out to run the test, define what “done” looks like. This could be a set time frame, a count of new signups, a number of total work hours elapsed, or monetary value reached.

- Starts with a hypothesis and ends with reflection. Before you begin an experiment, take time to gather notes on “what you think will happen” and “why you think that will happen. Then, after the experiment is all wrapped up, sit down and reflect. You need to set time aside to work on finding and interpreting the data as well as time for internalizing the results. Write it all up in a post mortem and share the notes with your team.

- Doesn’t create inequity.

- If you’re doing a price or promotion experiment, offer the discount to anyone who asks.

- And, before you run an experiment on price, think about how the change affects existing customers. As much as you might try to avoid it, your paying customers may see a deal and ask for it. As a company, we always match a discount for anyone who asks.

- If you’re experimenting to raise prices, your existing customers may be concerned that they, too, will have a price bump. We always maintain historic, lower prices for existing customers even through a price increase. There are people paying for our highest tier of membership (now $297 per year) for just $47. Obviously we could force these users to pay the full price or leave. But that’s not the kind of company I want to be.

- Isn’t illegal, unethical, or dangerous. Again, another broad statement. Avoid experimenting in areas you aren’t ethically comfortable changing. If an experiment tells you to engage in something that doesn’t sit well in your heart, that was a useless experiment.

Why are you running an experiment?

Why are you motivated to bother running an experiment at all? There is notable effort involved in designing, running, and reflecting on the outcome of experiments for your recurring subscription business. Sure, some experiments are very simple. But others require a lot of work.

So as you choose your first business experiment, think about how the outcome, how that “assumption validation” and new knowledge is going to make a positive contribution:

- Does the experiment help you make more money—whether through improved customer retention or new signup growth?

- Will you, your team, or your customers save time with the new and improved strategy?

- Does the experiment help you spend less money on your product support and development, customer acquisition cost, or content marketing efforts?

- Is this experiment a way to test an idea? To release an MVP, help you validate that a market exists for a non-existent product?

So what experiment are you going to do first?

At the start of this piece, we set the goal that you’d leave with a single business experiment to run in the next 30 days. To that end, here’s a list of 10 more unique experiment ideas. I hope something in this list both applies to your business and feels like something you can get going in the next 30 days.

- Just stop doing a thing you don’t like (within reason). If there’s a part of your business that you dislike doing, is there a way to just stop doing it? Case in point: we turned off blog comments on our PMPro site’s blog because no on enjoyed moderating them (and they needed moderation). Problem solved?

- A/B test subject lines (transactional emails, too). Don’t overlook the transactional email your business sends when testing subject lines.

- Add a free membership level. Is there something you can section off from your business and offer through a free membership website?

- Add or remove the paywall on something popular. Removing a paywall or allowing a limit of free post views is a great approach to letting non-paying members get a taste of your premium stuff.

- Offer pre-sales calls or call random customers. We tried it—it was interesting, deeply insightful, and can be really painless to just start trying.

- Repurpose Content: Make an eBook from 10 popular premium or free articles. Some paid membership sites are built entirely around delivering content in a better format. For example, a course version of what you’ve already published as standalone blog posts.

- Add your phone number or live chat to your website.

- Run a different kind of sale. We ran a sale once where we just threw the banner up on our site and didn’t email our list. We were testing how many people would buy the product just from the banner (it was not a good thing and we won’t do that again).

- Hire a freelancer, maybe 3 for the same project. If you have a back burner project you just cannot personally make the time for, could you hire someone to do it? Even to get it started?

- Take a 7 day vacation or staycation. Everyone benefits from taking a mental and emotional break from their business.